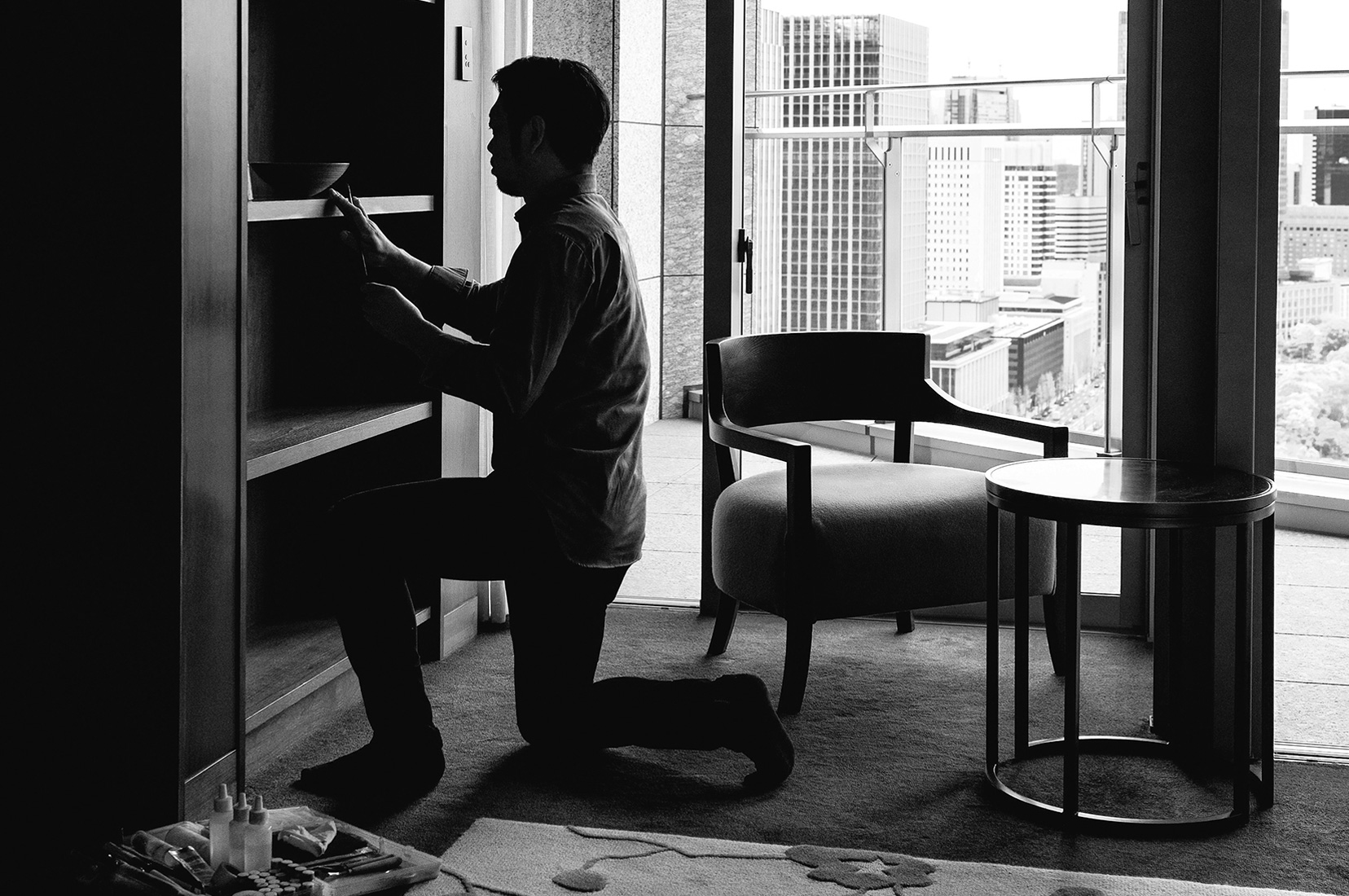

Shingo Izumi, chef of the hotel’s Japanese cuisine division, quickly and beautifully arranges, like a still-life painting, yuan-style grilled mackerel, conger eel-wrapped burdock root, baby sea bream sushi and other delicacies in a white-glazed, boat-shaped vessel over 50 centimeters wide. The ceramic dish is found nowhere on the market because Izumi kneaded the clay and fired it himself to be the perfect complement to the food. His job is to create a cuisine that delights customers. Japanese cooking, he insists, is not limited to selecting and preparing ingredients.

When young, Izumi liked to make things. In high school, he considered studying engineering at college. If a classmate had not invited him to a presentation given by a Japanese culinary institute, he probably would not be a chef today. He certainly liked to fish and would sometimes prepare what he caught for his family and friends, but he had no intention of going into the culinary arts professionally.

“If the school had only been geared to getting a cooking license and not to Japanese cuisine, I probably wouldn’t have gone. When my friend mentioned it, what resonated was not the cooking part, but the Japanese cuisine. I didn’t have strong feelings about it though; I was just a high schooler who liked to fish. But Japanese food is not just to fill your stomach, and making it is not the end of it either. You have to respect the flavors of the season and pay attention to the dishware and how the food is presented. The tools you use are also delicate and embody the chef ’s spirit. I sensed that Japanese cuisine was a multifaceted art form and a condensation of Japan’s view of nature and aesthetic sensibility. All sorts of making are involved. It seemed interesting to me.”

Kitaoji Rosanjin, one of the 20th century’s major artists and epicureans, prepared food himself and made dishes and vessels to present it. “Cooking is an art form,” he said, and “Dishes are the kimono of food”—he has numerous famous quotes on the subject.

Izumi, in his first year, studied the basics of Japanese cooking and then worked in the kitchen of a famous Japanese inn, ryokan. As a new member of the staff, his job was to retrieve dishware from the storage room for that day’s menu. He became as knowledgeable as anyone about what was located where and he soon absorbed the sensibility of the chefs and senior staff about how to pair the dishware and food. He continued to train as a chef and after ten years began working in the Japanese cuisine division of Palace Hotel Tokyo.

Izumi’s job is not limited to cooking. He is between the head chef and the division’s almost 40 cooks and assists the head chef in selecting seasonal and special menus, conveys them to the cooks and puts the finishing touches on the presentation. Selecting dishware and arranging the food are a major part of his job. With Western cuisine, plain white dishes, like a blank canvas, are standard. But Japanese food is different. A world must be expressed that encompasses both the season and the ingredients. When there is no dishware that will do, Izumi fires something himself.

He began studying ceramics not long after arriving at the hotel and he now makes plates, tea bowls and other dishware in his own kiln. From unglazed yakishime to oribe stoneware and sometsuke porcelain with brush-painted wildlife, his work is extensive. He has made over 1,000 items and some are used by the restaurant and lounge. When working out a menu for a large banquet, he wanted guests from overseas to enjoy the chawanmushi, a savory egg custard dish that is a hallmark of Japanese cuisine, so he fired vessels for each guest and delivered a meal of supreme hospitality.

Head chef Keiji Miyabe discusses Izumi’s work: “For Japanese cuisine, knowing the food is very important, but so is knowing the dishware. Japanese cuisine embodies aspects of Japanese culture, including its ceramic arts. I count on Izumi to pursue this art to the utmost. I expect the younger cooks to watch and learn from him as well.”

Izumi is also very particular about the knives he uses. He has over 20 blades varying in length, thickness and balance, and he uses different ones for different foods. No matter how tired he gets, he always sharpens the blades he used that day and puts them away in their case. He designed and made the wooden case himself from Japanese cypress. You can buy such cases, but he did not want to put his cherished knives in a synthetic leather container. He was not satisfied until he made his own.

Izumi began studying the tea ceremony four years ago. Invited by a ceramics friend to attend, he was utterly enchanted by its depth. “The appeal of Japanese cuisine is in the total experience, not just the food, and I realized it is all contained in the tea ceremony—mindfulness of the season and various thoughtful considerations for receiving the guests, spending time together as if a once-in-a-lifetime encounter, and seeing them off. This is the culmination of all I had thought about in the world of Japanese cuisine.” Izumi recently rebuilt his house and had an authentic tearoom created complete with a hearth. He plans to continue to study the essence of hospitality through the world of tea. While serving as a chef, he hopes to help carry on the beautiful traditions of Japanese cuisine.

Text: Arata Sakai

Photos: Yoshihiro Kawaguchi

This article is based on an article that appeared in THE PALACE Issue 03 published in February 2020 and contains information current as of February 2023. Please note that the article uses text and photos from 2020, and there may be some information that is not up to date.

More