It is evening at a patent law firm in Munich, Germany sometime in September 2022. Another busy day has come to a close, and the firm’s members are gathered in the lobby conversing with one another. On the wall behind them is a large world clock displaying the time in Munich, London, Paris, New York, Tokyo, and other world cities. They glance at it and talk animatedly about clients in other countries or where they want to take their next trip.

This world clock first told the time in another country some 9,000 kilometers from Germany, the country of Japan. When Palace Hotel, the predecessor of Palace Hotel Tokyo, opened in 1961, the clock was on the wall next to the lobby cloakroom. With a world map carved into wood panels and digital readouts showing the time in 10 cities, both the design and technology were groundbreaking. In 1964, three years after the hotel opened, the Olympics were held in Tokyo and all of Japan was buzzing with excitement. Restrictions on overseas travel were lifted and the distance between Japan and the rest of the world was beginning to shrink. The clock was made during that era and became a symbol of the hotel. Many global financiers stayed there, and in their finely tailored suits, they followed trends in global markets while checking the clock. On Fridays, the lobby bar overflowed with patrons talking and milling about, enjoying a beer and a steak sandwich; it was lively, almost like Wall Street perhaps, and the clock was there ticking on.

Half a century later this world clock would cross the seas from Japan and arrive at a patent law firm in Munich.

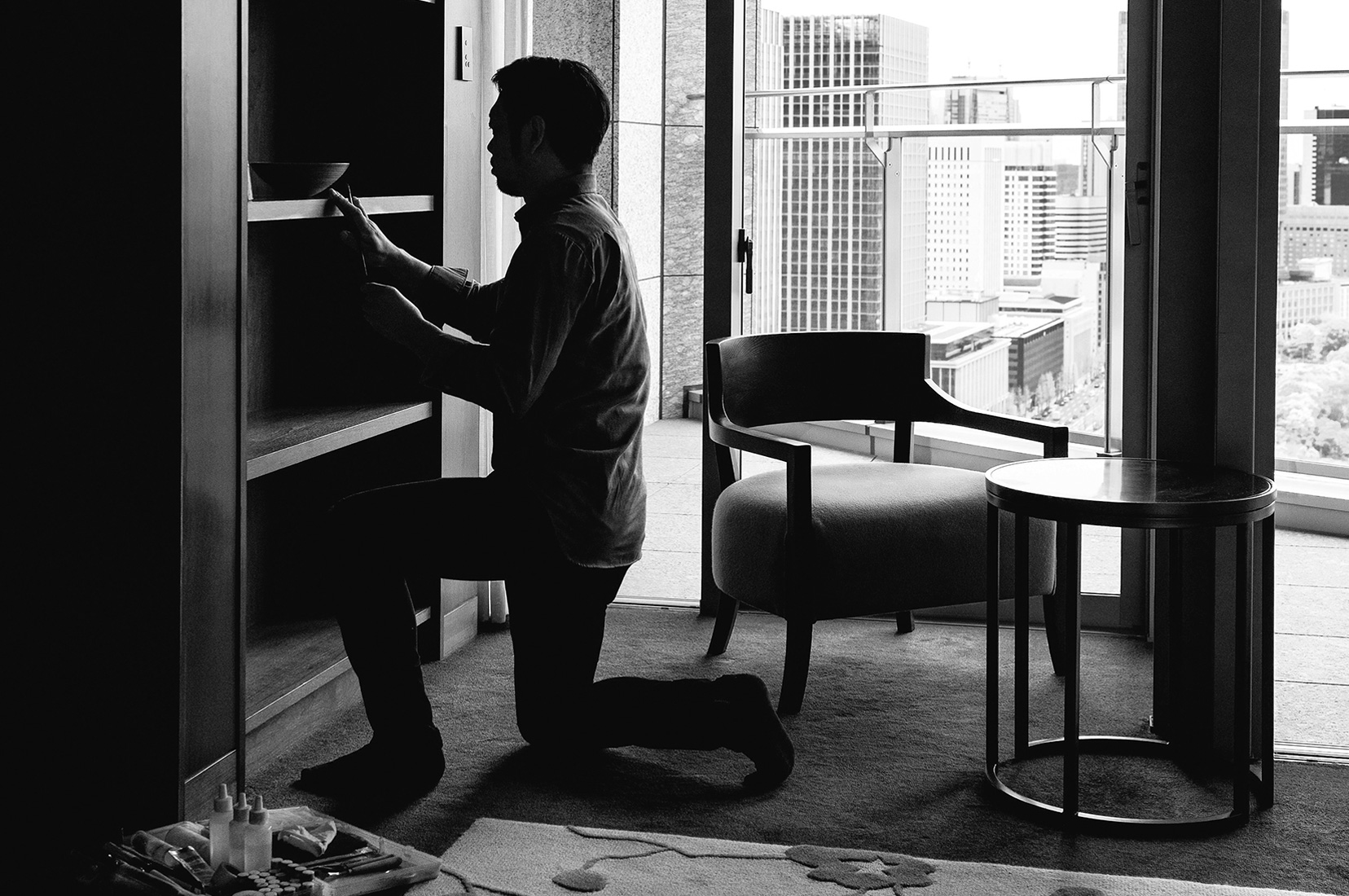

Palace Hotel closed for rebuilding in 2009, its 48th year. The worldclock, beloved by guests and the hotel staff alike as the face of the hotel, was not in the plans for the new Palace Hotel Tokyo when it was to open in 2012, so there was talk of discarding it. Some of the staff who had lovingly used the clock to tell the time for many years were adamant about keeping it, but old mechanical clocks can be difficult to maintain because parts and repairers are so hard to find. The time to say goodbye to this long-serving “colleague” of the staff that had kept watch for so many years over guests had finally come.

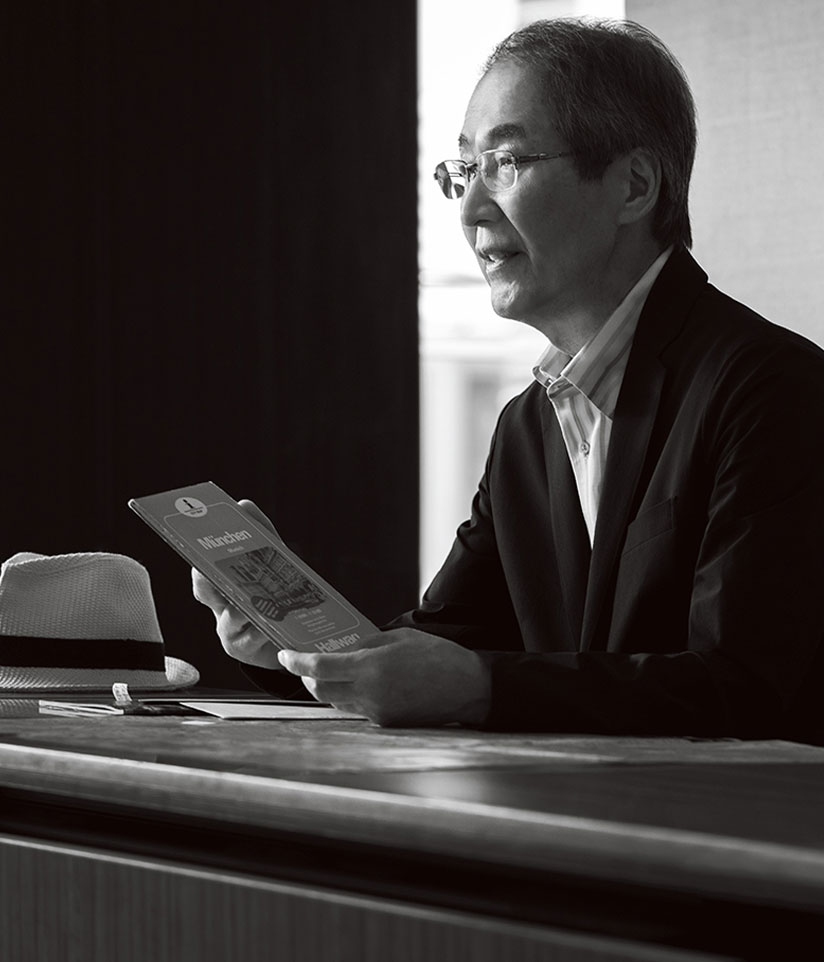

An offer, though, came in unexpectedly to preserve the clock. The message was delivered to Yasuji Fujita, who was an advisor to the hotel. Paul Tauchner, a partner at the patent law firm in Munich, Germany, had made it. Paul and his associates had done business with Japanese companies and had stayed at the hotel for almost 40 years. As an art collector with a great deal of knowledge, Paul took note of the clock on his stays and was interested in its unique art déco design that resembled a cut-up orange. Fujita recalls.

“Paul and many others at the firm,” Fujita says, “loved staying at the hotel and we developed a real friendship. When I told him upon a visit that the hotel was going to be renovated, he was truly shocked. And when he found out the new hotel would not be displaying the world clock, he was clearly disappointed and began wondering whether it would be possible for his firm to acquire it.”

After Paul made his offer, Fujita immediately took the matter to the company. It was a large item that was not necessarily easy to hand over, and it was not entirely clear how it would be done. Paul was a longtime guest of the hotel however, and Fujita wanted him to have the clock, so discussions took place with others involved at the company. “Making every effort to meet guests’ requests is the basic credo of a hotelier,” Fujita says. “I recalled what the president had told me when I joined the company: ‘A hotelier must not just interact with guests from behind the counter, he must get out and get to know them.’ I talked with people around the company with these words in mind.”

His efforts bore fruit, and it was decided that the clock would be transferred to the firm, and Paul was elated when he heard the news from Fujita.

In January 2009, the hotel closed its doors. On its very last day, members of the firm came to Japan for a reluctant farewell. Looking back, Paul says, “We were able to find dedicated movers in Japan to ship the clock, but I wanted to express our appreciation for the fact that we were allowed to receive this important piece of history from Palace Hotel. My colleagues tell me that the greeting they received in front of the elevator was a very memorable moment.”

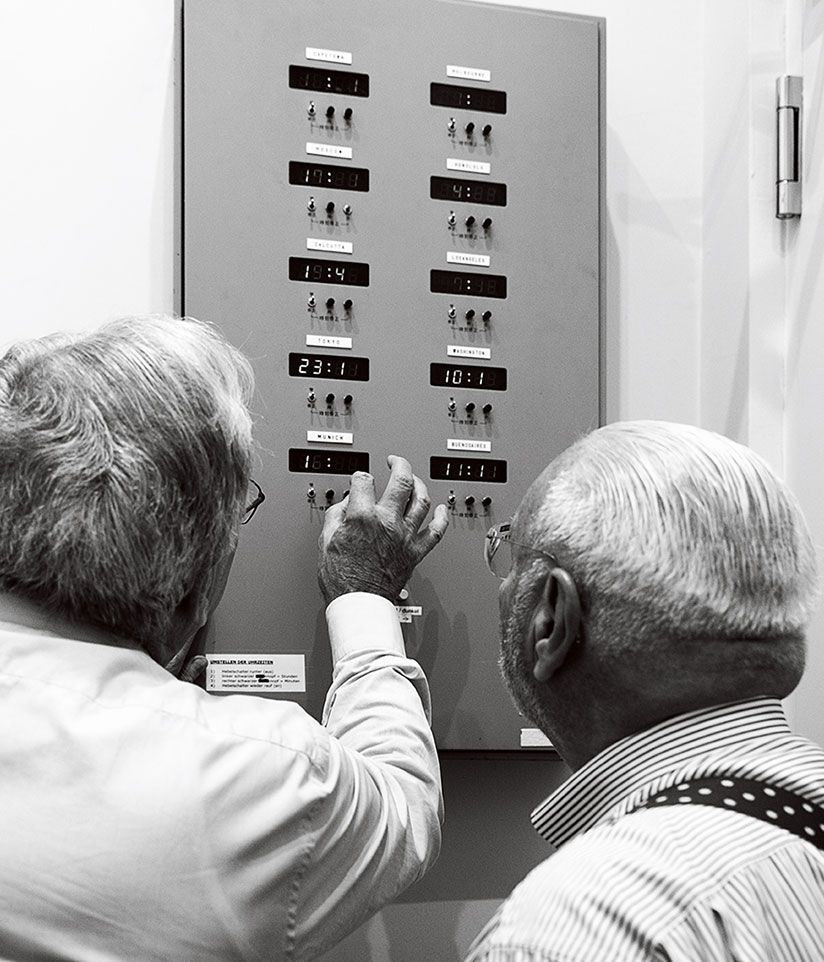

The clock was taken down the day after the hotel closed. Packaging the six large wood panels and disassembled control panel was a considerable job in itself. And even after the clock’s arrival in Munich, there was still work left to be done. It was impossible to tell who manufactured it, and there were no wiring diagrams or other helpful guides, but partners in the firm who were specialists in physics, engineering and IT carefully performed the task while working out the intricacies of the control panel. This ended up taking around two years to complete. The digital time displays, which used vacuum tubes, were replaced with digital LED lights. Other adjustments proceeded by trial and error until finally, in March 2011, the world clock was ticking again in Germany.

“Munich was not among the 34 cities shown on the original clock,” Paul says, “so we added the letters for it. The clock gets behind during Daylight Saving Time in the summer, so it’s still not perfect, but this clock in the entrance lobby of our office is the face of the firm ― even today it welcomes in important clients. Our company was founded in 1961, the same year Palace Hotel opened. It may only be a coincidence, but I feel somehow that we have a very deep connection.”

A world clock made in Japan and now ticking overseas, connecting people, connecting past and future, continues to tell the time in the here and now, in this rich and irreplaceable moment.

Text: Ayako Watanabe

Photos: Sadato Ishizuka

This article is based on an article that appeared in THE PALACE Issue 06 published in February 2023 and contains information current as of February 2024. Please note that the article uses text and photos from 2023, and there may be some information that is not up to date.

More